A Gentler Way to Cool a Throbbing Migraine (that lasts for hours)

We’re always on the lookout for a better way to cool down the throbbing pain of a migraine attack.

There are many ways to “cool your head”, and they all have their pros and cons. Of course there are the old ice packs – some better than others. But the temperature can’t be controlled, and it’s hard to keep them in place.

There are “wearable” ice packs too – better, because they will stay in place and are adjustable.

Also there are professional grade cooling systems, such as the ThermaZone Continuous Thermal Therapy Device that gives constant cooling. An excellent option, but a professional device comes at a professional price.

But if you want an inexpensive solution, gentler than an ice pack, it’s the simple, wearable “cooling pads” that are getting the rave reviews (at least, some brands).

But if you want an inexpensive solution, gentler than an ice pack, it’s the simple, wearable “cooling pads” that are getting the rave reviews (at least, some brands).

These pads generally come filled with a gel, and you can press them on your forehead or the back or your neck (they have a gentle adhesive), and they’ll work in some cases for hours.

Probably the most popular and highest rated is the BeKoool brand (just say the name a few times and you’ll feel better 😉 ). One of the reviewers from last year wrote this:

I seriously wish I’d heard of these years ago. They feel similar to using a Badger Headache Soother Stick, except the results last for hours instead of just mere seconds). These gel sheets are FAR superior to a washcloth or ice pack; they are practically weightless for starters (any pressure on my head is unbearable once a migraine has started), and they maintain the same cool temperate for a full 8 hours, unlike a washcloth which only stays cool for five minutes, or an ice pack which starts off too cold and needs to be wrapped, then needs to be continually unwrapped to maintain the same coolness over the next hour or two (and the last thing you want to do when you have a migraine is move, because that just makes your head throb worse).

If you want to stay elevated, or if your pain is minor and you want to move around, or if you roll around a lot when you’re in pain, these are amazing because they stay in place wonderfully! I’ve gone to sleep wearing them (I have a hard time falling asleep when my head hurts and these help so much) and even though I toss and turn, these strips are still in place when I wake up hours later.

These are by no means a miracle cure – they don’t stop my headaches or migraines. However, if I use one while waiting for my Relpax to kick in, it makes the wait FAR more bearable. I will definitely be stocking up on these. I’m honestly considering getting bangs just so I can wear these discreetly out in public without getting strange looks! No, I’m not joking, that’s how much I love the way these feel!

[source]

The main complaints come from two sources – one, the scent. Which is why BeKoool for Migraine is great because reviewers tell us they have no scent. (The MQ brand, on the other hand, apparently has a nasty scent. Avoid that one!)

Some people also find that the adhesive is irritating. That isn’t the case for most people, but you may want to try out a brand before you buy 50 boxes to have on hand.

Also well reviewed is the WellPatch Migraine & Headache Cooling Patch (which claims to last up to 12 hours) and the Coralite Cooling Headache Pads.

By the way, the company that makes BeKoool specializes in this type of medical pad. They also make pads for soothing fever in children.

These are an excellent drug-free way to soothe symptoms. I can also see them being a great surprise gift to send to a friend who gets frequent headaches.

What is officially called short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks is actually one type of chronic daily headache. The headaches last only seconds or minutes (as long as ten minutes), but they are very painful and hit you at least once a day. The pain is on one side of the head, and the eye on that side will usually get red and watery.

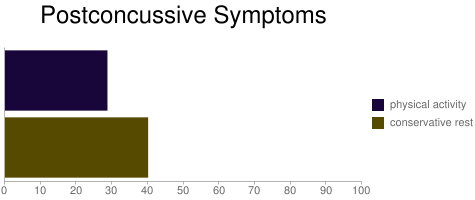

What is officially called short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks is actually one type of chronic daily headache. The headaches last only seconds or minutes (as long as ten minutes), but they are very painful and hit you at least once a day. The pain is on one side of the head, and the eye on that side will usually get red and watery. As you can see from the chart, those who went back to physical activity within 7 days were significantly less likely to have the unwanted symptoms.

As you can see from the chart, those who went back to physical activity within 7 days were significantly less likely to have the unwanted symptoms.